Social Transformation

The first thing I noticed, when I began to study objects which have life, was that they all contain different scales. In my new language, I would now say that the centers these objects are made of tend to have a beautiful range of sizes, and that these sizes exist in a series of well-marked levels, with definite jumps between them.

“In short,” further explains Alexander in his book, The Phenomenon of Life: Nature of Order,

there are

big centers, middle-sized centers, small centers, and very small centers. In the language I used at that time,

I would simply have said that I noticed a great variety of well-formed wholes of many different sizes

and that this was often the first thing one noticed about those things which have great life in them.

One of the main tasks of enterprise (re)engineering is to define appropriate levels of scale and design balanced, flexible, and adaptable structures at each level, where each structure is implemented as a network of strong centers capable of performing complex computational activities.

The enterprise can use principles of the enterprise engineering framework (EEF) to execute the social transformation phase of enterprise reengineering. This phase establishes the human architecture of the enterprise by creating a clear and elegant two-level enterprise structure. This sets the scene for further enterprise transformation, which includes formalization of units' boundaries, optimization of enterprise coordination and enterprise communication, and internal transformation of each enterprise unit.

The Current State

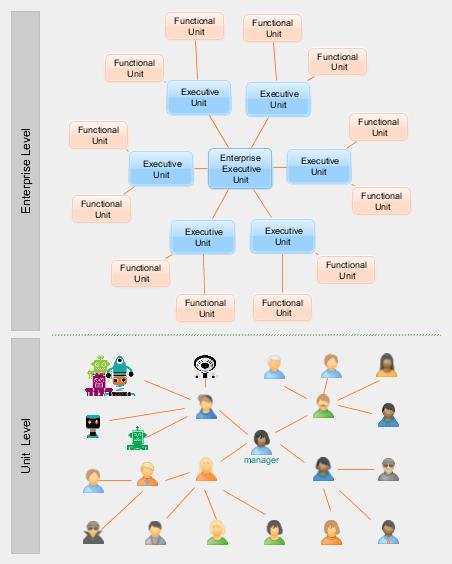

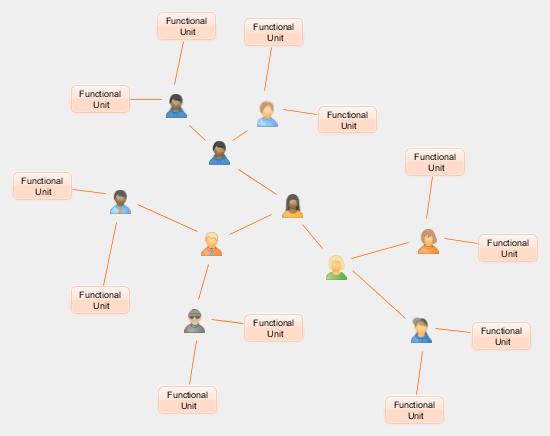

Figure 2.2 shows a flattened structure of a contemporary enterprise, which is traditionally

viewed as a multi-level hierarchy with power, control, and access to resources unevenly distributed between the levels of the hierarchy.

Although—as some studies

show—hierarchy is absolutely inevitable, and hierarchical organization of the enterprise has obvious advantages,

from the enterprise engineering perspective, the classic Taylorist org-chart view of the enterprise

has caused so much unnecessary ambiguity and confusion that, according to John A. Zachman, even though

IT has been

manufacturing the Enterprise (building systems) for 70 years or so... the Enterprise was never engineered.

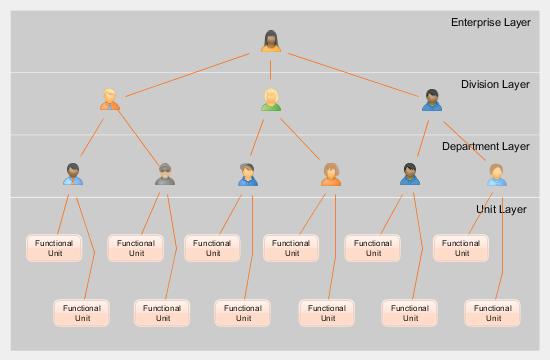

If we believe that after 100+ years since Taylor laid the foundation for scientific management the second decade of the 21st century is the right time for engineering the Enterprise (creating digital constructs for the Enterprise itself), then we should consider building the Enterprise as either (1) a layered construct, (2) a nested construct, or (3) a networked construct:

- Enterprise as a layered construct. Because of the org-chart bias, many would choose a

layered architecture approach to enterprise engineering. Even though this approach offers several advantages in terms of

loose coupling, minimizing dependencies, and improving manageability, it also creates negative effects on collaboration, coordination,

and communication between enterprise components (and between the components and the environment)

by introducing additional overhead of communicating through layers.

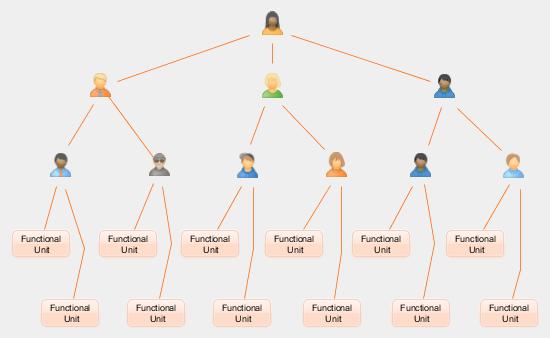

Figure 2.3. Enterprise as a layered construct. - Enterprise as a nested construct. This approach was influenced by business capability mapping,

the technique that results in creation of a business capability map—a nested hierarchy of business capabilities,

which often looks similar to one on Figure 2.4.

The article by Ulrich Homann,

a Distinguished Architect at Microsoft, illustrates the process of modeling Business Capabilities (level 3)

nested inside Capability Groups (level 2), which are in turn nested inside Foundation Capabilities (level 1).

This approach is rather useful for communicating ideas about business capability architecture; however,

it creates a false impression of the containment/nesting of enterprise components inside other enterprise components.

Figure 2.4. Enterprise as a nested construct. - Enterprise as a networked construct. Engineering the Enterprise as a network emphasizes modularity

as the best strategy for organizing complex systems. The history of evolution shows that when an artificial or a biological system

becomes more modular, it also becomes significantly more adaptive and agile. In addition, the Enterprise implemented as a

modular network can more effectively integrate into the global business environment.

Figure 2.5. Enterprise as a networked construct.

The Future State

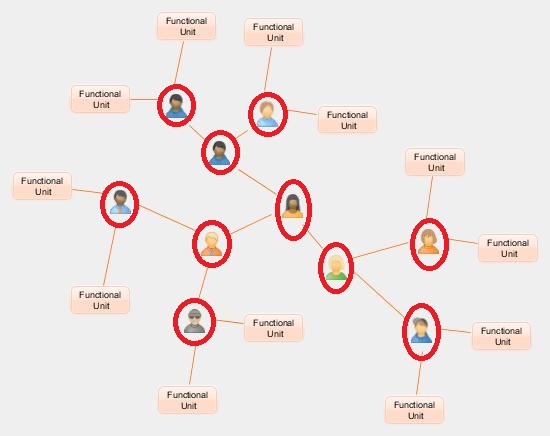

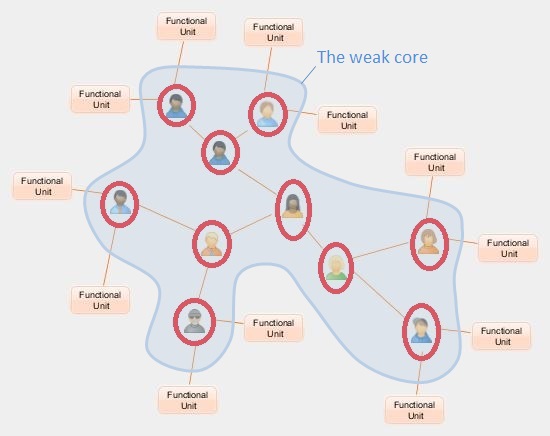

It doesn't take more than a quick look at Figure 2.5 to notice that the network construct contains not only strong centers, but also weak centers (human agents), marked red on the following diagram.

As mentioned earlier, hierarchy is inevitable, and (orange) links on the diagram signify hierarchical relationships between the centers. Even in the flat hierarchy shown on the diagram, the "higher level" centers become responsible (and accountable) for "lower level" centers contributing their best to the success of the whole. Ironically, the executive core that is responsible for the success of the entire enterprise, in most, if not all organizations, is implemented as a network of weak centers.

Weak centers negatively affect the effectiveness and efficiency of enterprise functioning because they (1) have limited computational capability, (2) cannot ensure sufficient quality of service (availability, response time, reliability, performance, etc.), (3) slow down information flow, (4) fail to establish formal decision interfaces, and (5) fail to record, maintain, and learn from the history of their decisions.

The EEF solves these problems strengthening or aggregating several existing weak centers into more complex strong centers called units.

The Process

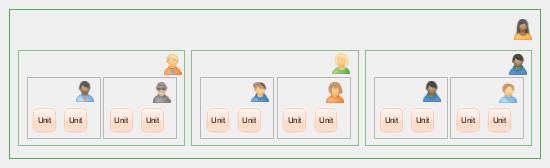

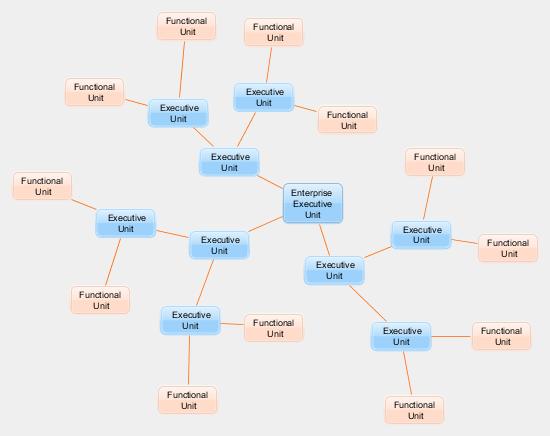

Social transformation is a recursive decomposition of the Enterprise into a network of executive and functional units—a process that can be qualitatively explained as follows:

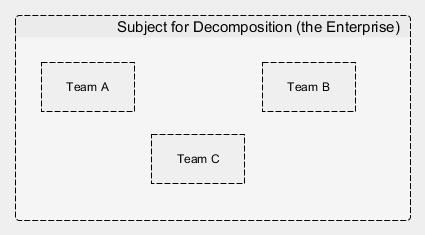

- Rule #1 (prepare for decomposition).

Begin with a monolithic unit (the Enterprise) and mark it with Subject for Decomposition.

Figure 2.8. Mark the Enterprise with "Subject for Decomposition". - Rule #2 (decomposition step).

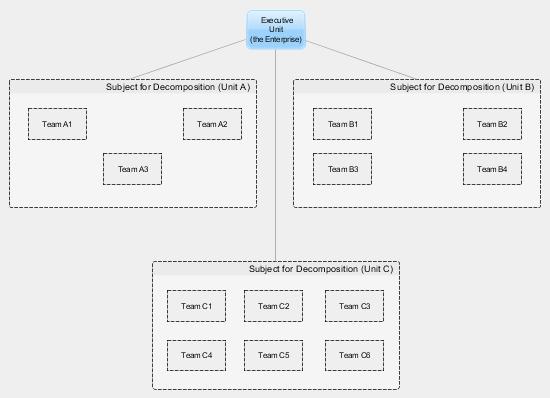

Take any unit marked with Subject for Decomposition and decide whether to decompose it or not.

It usually comes down to the decision of whether to (1) externalize the unit's teams and create formal boundaries

around them (decompose) or (2) keep the teams without formal boundaries inside the unit,

which makes it easy to create virtual teams (not decompose).

If you have decided to decompose, the Subject for Decomposition becomes an Executive Unit; the externalized units become Subjects for Decomposition as shown on Figure 2.9.

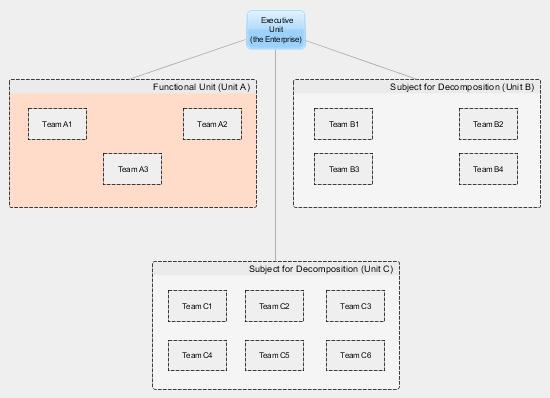

Figure 2.9. Decomposing a unit. If you have decided to not decompose, the Subject for Decomposition simply becomes a Functional Unit: nothing else needs to be done. For instance, Figure 2.10 illustrates the decision to not decompose the Unit A (made during the next recursion).

Figure 2.10. Deciding to not decompose the Unit A. - Rule #3 (recursion). Repeat Rule #2 until no more Subjects for Decomposition remain.

The result of the completed recursive decomposition should look similar to one on Figure 2.7—a network of strong centers with the executive core and functional periphery.

Benefits of Social Transformation

The main goal of the social transformation phase of enterprise transformation is to reduce the complexity of the Enterprise. Social transformation

- Streamlines the human architecture of the Enterprise by reducing the number of levels of scale to two. The enterprise level is constructed as a network of composite agents (units); the unit level, as a network of individual agents;

- Eliminates weak centers from the enterprise level. The weak centers are combined and developed into strong computational centers capable of providing the desired quality of service;

- Accelerates information flow. The introduction of strengthened and coarse grained information processing centers at the enterprise level not only increases the speed of but also reduces the volume of the information flow.